Explaining Why Music Critics Tried to Cancel Lana Del Rey

A wayback machine into the birth of indie pop's most polarizing superstar

AIR GUITAR is a 100% reader-supported publication. Each issue is researched, written, and edited by Art Tavana. If you want more AIR GUITAR, please support it as a paid subscriber.

AIR GUITAR #1 🤘🏻

“All the good stuff is real but isn’t, myself included…I mainly let my imagination be my reality. Fantasy is my reality.” - Lana Del Rey (HuffPost, 2010)

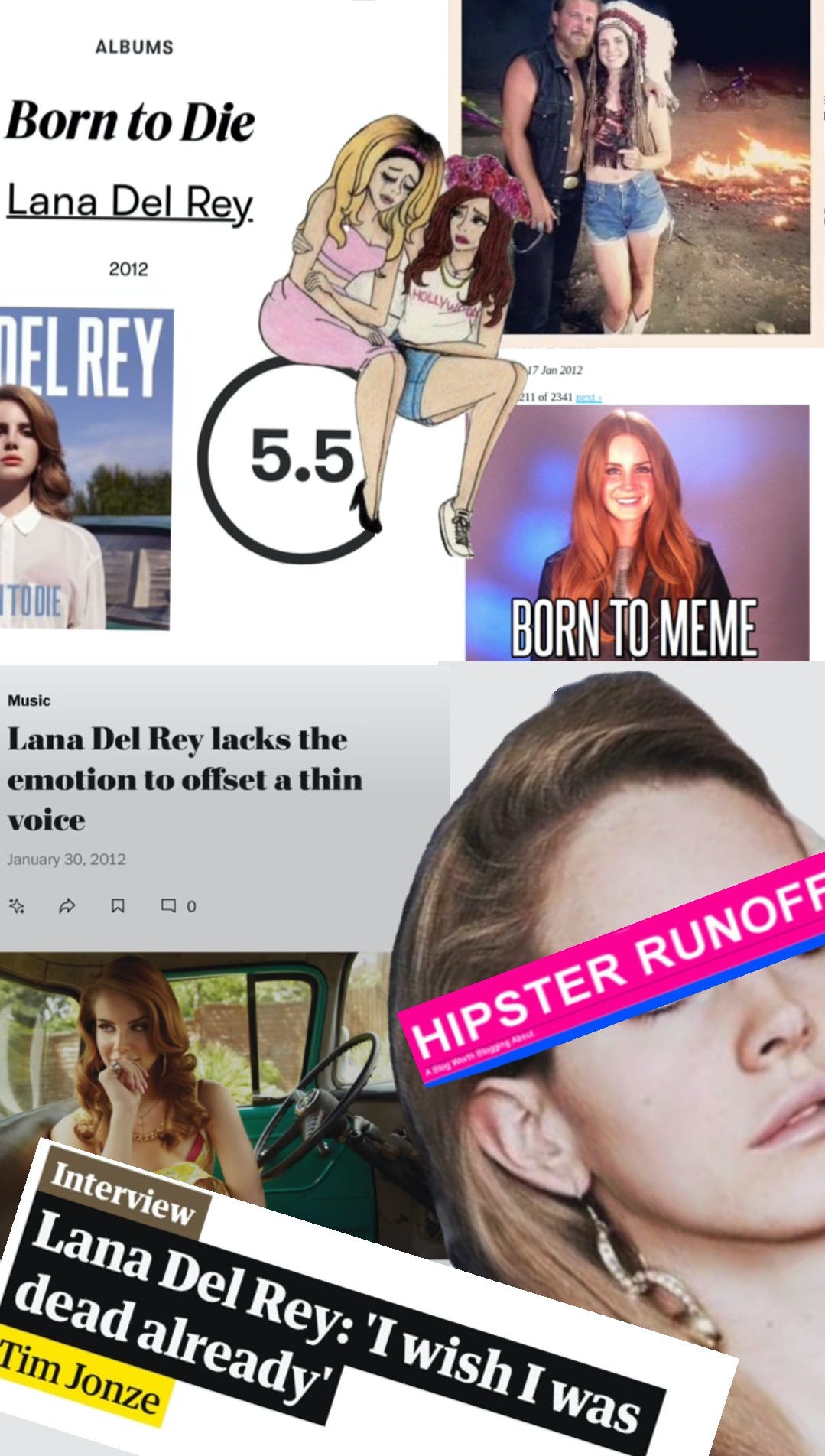

“Peak Hipster” (2007-2014) was defined by gatekeeping in the arts: the blurring of lines between cultural preservation and cultural authoritarianism, e.g., agenda-driven music bloggers deciding which artists they would vilify (e.g., Lana Del Rey) or sanctify (e.g., Lorde).

Here’s a headline from 2012, the year LDR crossed over from ”MP3-blog viral” to mainstream viral: “Why Hipsters Hate On Lana Del Rey” (Pacific Standard, 2012), which argued that music bloggers turned on LDR the moment they discovered she was once a blonde, All-American-looking pop singer named Lizzy Grant — an identity she had “wiped” off the internet (according to her own producer).

We’ll get back to #LizzyGrantGate, but for those of you too young to remember, back in 2012, the music bloggers had drawn clearly defined borders separated indie from pop, and LDR was border hopping. “Of all the upheavals in music over the last 10 years,” wrote Jayson Greene for Pitchfork in 2019, “perhaps none was broader or more permanent than the complete erasure of the borders around ‘indie music.’ The twin financial and ideological barriers separating those two words began to collapse, brick by brick.”

As of the 2010s, when music bloggers replaced MTV’s tastemakers, they lifted “ideological barriers” between indie and pop. For example, if LDR had released “Video Games” in 1997, it would have been a video on MTV, like Fiona Apple’s heroin chic, flash photography-produced “Criminal.” MTV would never have interrogated her “authenticity.” She would have been like Amy Winhouse in the mid-aughts: a pop balladeer who looked rockabilly and retro — “a bad girl with a touch of genius” (New York Times, 2011). The “indiefied” 2010s were different. If Fiona Apple had released “Criminal” in 2011 as a viral YouTube video, the music bloggers would have questioned the “authenticity” of an artist who was interbreeding indie aesthetics with pop sensibilities (supported by a major label).

Note: LDR first came to New York in the mid-aughts as Lizzy Grant, performing open-mic nights with the likes of Lady Gaga aka Stefani Germanotta. But while Lady Gaga groped for pop success — never hiding her ambitions to be a star — LDR was caught somewhere between indie and pop, which presented a dilemma for music bloggers who had had codified distinctions between pop stars like Lady Gaga and DIY artists like Best Coast or GarageBand-era Grimes.

Here’s Sasha Frere-Jones in The New Yorker, 2012: ”People seem to feel that Del Rey is trying to trick us, though it’s impossible to figure out exactly what that trick would be, as we are dealing with an entertainer and her audience, not a naturally fractious relationship.”

The “trick” was that LDR was signed to a major label, but she looked and sounded “indie.” She was caught between indie and pop, which is why Greene’s omission of LDR from his indie-pop history is surprising. But the history of how indie went pop, and pop went indie is the history of pioneers like LDR, Grimes, Charli XCX, Lorde, and Sky Ferreira, who in 2012 rejected having her indie pop ascent compared to LDR’s — a way of solidifying her indie cred and pushing back against the idea that she was the “next Britney Spears”: “I don't know anything about Lana Del Rey,” she told Pitchfork, “but I'm sure there are people thinking that's the angle the label's trying to take with me now."

But what angle? To answer that, we need to go back to when the music bloggers discovered LDR — the pre-history of the Born to Die-era: June 29, 2011, the day LDR released “Video Games” on the internet (the track, not the video). By August, the track had gone “MP3-blog viral” when BBC’s Radio 1 played it in rotation; Pitchfork followed by naming “Video Games” a “Best New Track” (Pitchfork, 2011), which is notable as it demonstrated how the bloggers felt about LDR before she was “exposed” as Lizzy Grant.

As reported at the time, in June of 2011, LDR had moved from 5 Points Records (her original label) to Stranger Records in the UK — her managers negotiating her out of her deal with 5 Points — and by October, she was “dully signed by Interscope [and Polydor in UK], which released 'Video Games' officially and saw it climb to the top 10 in the UK and half a dozen other European countries” (SoundonSound, 2012).

This negotiated transition from an indie to a major raised some red flags. Music bloggers were vibing on the sonic dreamscape of “Video Games” while hate-reading tweets and blogs suggesting that LDR was an “industry plant” who had signed to Interscope four-to-six months prior the original announcement (according to Billboard). Was she hiding something? That was a question, at the time, which coincided with her management and PR sloppily handling her transition from indie to pop. When the original video edit for the “Video Games” was self-released on June 29, 2011 (“Video Games,” 2011), it was promptly taken down, and then re-released on August 19, 2019 by her label, which was again taken down/edited into a new version in October.

Online sleuths discovered that the reason for taking down “Video Games,” according to The Portland Mercury, was that the original video contained copyrighted material by musician/artist Ryland Bouchard (The Portland Mercury, 2011). The Portland Mercury reported that, “Del Rey video apparently made liberal use of Bouchard's short film ‘Good Life #2.’ Bouchard sent a request to Del Rey's people to cease and desist; they didn't because (as some sources indicate) it would draw too much attention to the fact that the footage was stolen. The video has since been re-edited without Bouchard's footage, and the video's current YouTube page credits where all the remaining footage came from.”

In other words, LDR’s “people” had gained clearance of the copyrighted material and reshared the video. The editing of the video was DIY, but its release was a bit more complicated.

Note: As far as I’m concerned, as of 2011-12, LDR was a pop star. The “authenticity” arguments are irrelevant to me. She was a pop star with major label backing (which does not invalidate her artistic talent).

On July 15, 2011, MTV Style praised LDR as, “ZOMG she is so important,” which isn’t important except that MTV Style ran with the moniker “Gangsta’ Nancy Sinatra.” The music bloggers did not like that, placing scolding-hot quotation marks around “Gangsta’ Nancy Sinatra” and branding her with it: “Lana Del Rey is certainly no ‘gangster Nancy Sinatra, or gangster anything, really (Entertainment Weekly, 2012); “I really wish she hadn't taken it there with this whole ‘gangsta Nancy Sinatra’ thing” (Pitchfork, 2011).

“I spend eight fucking years writing gorgeous songs and someone in a meeting says ‘gangsta’ Nancy Sinatra’ and that’s that,” she told DAZED in 2011. “It just goes to show how fucking stupid people can be sometimes.”

Music bloggers are empowered by discovering talent and codifying their appeal; they’re in the vanguard of the music labeling process — the internet is their record store. LDR was labeling herself as “Gangta’ Nancy Sinatra” (a moniker her label had posted to her YouTube page), which synthesized her mixture of hip-hop with Sinatra-esque balladry. Music bloggers didn’t know, at the time, that “Gangsta’ Nancy Sinatra” was her label’s cheesy tagline (DAZED, 2011). They just heard her telling them what she sounded like: “Hollywood Sad Core,” “Hawaiian Glam Metal” or “Lolita Got Lost in the Hood,” disempowering them from being able to control the narrative. “The phrase [‘Lolita Got Lost in the Hood’] sounded like a well-rehearsed product of the same elevator-pitch brainstorming session that brought us her primary tagline,” wrote Nitsuh Abebe in Pitchfork, adding that, “Del Rey has the ear and ambition for a pop audience, and an aesthetic that makes an effective splash around the ‘indie’ press.”

By the end of summer 2011, the buzz for “Video Games” was producing feedback that was getting louder and more distorted. The Portland Mercury described “Video Games” as a “remarkable debut for an unknown artist, and while she looks totally glammed-out to the point of artificiality (is that collagen? I'm just asking), that's never stopped a pop star before.”

The more popular LDR got, the more tabloid fodder she produced. The bloggers began to obsess over her face, which was flamboyant, especially for an indie artist; her bee-stung lips evoked ostentatious movie star, not stripped-down folk singer. In the comments section of the HuffPost review — 10 days after The Portland Mercury report — users commented that LDR didn’t “hold a candle” to Amy Winehouse, with a lot of the comments focusing on LDR’s lips (HuffPost, 2011).

The lips weren’t just “fake,” they were the dots that connected the conspiracy theory that she was “fake.” While Amy Winehouse was unfairly criticized by the tabloids, especially in the UK, she was never body shamed like LDR — whose body was used to smear her artistry.

On September 12, 2011, Hipster Runoff’s Carlos Perez reported on Lana Del Rey for the first time, asking, “Is Lana Del Rey the next overrated, marginally talented totally hot female in indie?” The next day, Perez “exposed” her as Lizzy Grant, pointing directly at her lips: “B4 she was alt,” he wrote, “she was a failed mainstream artist without fake lips — will she fool the Indiesphere?”

The Guardian (and others) ran with the Hipster Runoff “expose” and declared that “Lizzy Grant was a flop,” and that LDR was “nothing like Grant” (a patently false claim) and noted that photo comparisons of Lizzy Grant and LDR verified their suspicions that LDR had cosmetic surgery. She had changed her name (her debut full-length album in 2010 was titled Lana Del Rey by Lizzy Grant) and her face, like some “carefully constructed display” (FADER, 2014), a “concept human” (Pitchfork, 2014), “corporate-engineered” (Insider, 2011), or whether a major label had been “silently orchestrating one of 2011's greatest indie viral success stories?” (Billboard, 2012).

Note: Between September 2011 and January 2012, Hipster Runoff ran 29 hit pieces on LDR. LDR had become his hipster tabloid queen.

Bloggers also discovered old MySpace pages, including one from 2008 listing her as “Sparkle Jump Rope Queen” who spent “two years as a trapeze artist in a southern California circus.” Later they discovered “May Jailor,” the acoustic singer-songwriter who recorded a demo between 2005 and 2006 titled Sirens (which leaked online in 2012).

Lana Del Rey, one of the first internet-made pop stars, had different usernames and performative identifies — she wore looks like avatars — but the soul the artist belonged to the same person: Elizabeth Grant aka Lizzy Grant aka Lana Del Rey.

"The Internet's been well-established for 14 years," LDR told Billboard in 2012. "It's not like 1962 where you can't find out about me. My intention was never to transform into a different person. What other people think of me is none of my business.”

“We crave a popstar who is authentic,” wrote Rosie Swash in The Guardian, “who thrives because of their talent, not PR. So when you stumble across someone like Lana Del Rey — her popularity apparently born online and growing per YouTube click — it's hard not to be skeptical as to whether she's actually too good to be true. Surely it can't be that after posting just one song online (“Video Games”), this brand new artist sold out a London gig in half an hour?”

Music bloggers in 2010s viewed the internet with suspicion, and there was actually some evidence that LDR had wiped Lizzy Grant off the internet, e.g., her 2010 debut full-length, mostly completed by 2008 with mega-producer David Kahne (Paul McCartney and The Strokes), was no longer live. LDR didn’t spin this, telling Pitchfork that the album had been deleted off iTunes: “I would like people focused on my new music for now.”

But Kahne caused more speculation when he told Billboard that “[Her team] wanted it out of circulation. That's why they bought the rights from them,” adding that “she wanted to be Lana Del Rey and didn’t want to be Lizzy Grant. She wiped [out] this other person. I think she actually thinks that she’s that other person.”

Note: Kahne hasn’t worked with LDR since 2008. I also have to say that deleting old posts — which is what she was doing — is not erasing your past. It’s using the edit button; it’s an artist painting over their own portrait. Erasure is only when you deny that person ever existed (LDR never did that).

But music bloggers ran with the narrative that the Lizzy Grant debut had “flopped,” which is why it was removed off iTunes two months after its release — rewriting her past in the process.

The Guardian wrote that, “Grant looked like any one of hundreds of young artists trying to make it in the clubs and bars of New York, singing their hearts out in the hope that one day they would be spotted. After all, that's how big names from Bob Dylan to Lady Gaga got their breaks. But success never happened to Lizzy Grant. Her one and only album sank virtually without trace.”

It was the internet equivalent of Norma Jean “dying” and being born again as Marilyn Monroe. The difference is that Hollywood actually preferred the glamorous fiction to the “authentic” and plainer “untheatrical world [of indie] — an earnest, ‘gimmick’— free space that doesn't accommodate much in the way of creative personas. The whole genre is damn near allergic to pretense”[Pitchfork, 2011].

Here’s how LDR responded to the “authenticity” criticism in GQ, 2011: “It’s not like I planned on erasing my history. I’ve been a pioneer of the Internet myself since a decade ago. I was just trying to create something sonically that I could aspire to. First of all, no one was even listening to me for ages, so I did whatever I wanted. I had no fans, the same bands I’ve talked to for five years, and all of a sudden, everything changed, and they were like, ‘You used to be like...’ The point is, I know what I like and what to write about thematically and I have integrity in my musical choices and I’ve stuck to that and I think it’s a nice gift for me because I have stuck to my guns about what I want to hear sonically, so at least I’ve done that right. I’ve made the record I like.”

Note: Lo-fi or “plainer music” by Lizzy Grant (what GQ described as her “less exotic government name”) have been on the internet since 2008. Tracks like “Pawn Shop Blues” and “Yayo” (written between 2007 and 2008) don’t present drastic sonic departures from the demos that would become Born to Die (2012). Her debut music video “Kill Kill” (released in 2009 off her debut three-track EP, Kill Kill, from 2008) employed similar edits and aesthetic touch points found in “Video Games”: grainy camcorder footage of American landscapes and closeups of her face.

LDR candidly admitted, “Lana Del Rey came from a series of managers and lawyers over the last five years who wanted a name that they thought better fit the sound of the music,” she told HuffPost in 2010.

“My music was always kind of cinematic so they wanted a name that reflected the glamour of the sound.”

Note: The name “Lana Del Rey” was a combination of actress Lana Turner and the Ford Del Rey sedan, which was produced and sold in Brazil in the ‘80s. Not sure who “cooked that up,” but that’s what I found.

On the debate of whether she was really Lizzy or Lana, LDR told Pitchfork that there was no “real me and another me. Same person, just a different name.” David Nichtern, founder of 5 Points Records (LDR’s label from 2007-2010) said that LDR’s 2010 rebrand was entirely her idea: ”If she is ‘made up’ — well, she is the one who made herself up.” Her Told MTV Hive in 2012 that, “She [LDR] wanted to be known as Lana Del Rey pretty early on. That was her name, she cooked that up.”

But it didn’t matter that “Lana Del Rey” was her invention. Hipster Runoff (and other hipster tabloids) fueled the rumor that her dad (Rob Grant) was a “millionaire” record label executive (he was an advertising copywriter/successful domain investor) who was funding and coordinating her career — that he purchased her record label contract — which became part of LDR’s mythology as a sugar daddy-funded “nepo baby.” In reality, LDR’s managers had negotiated her out of her contract with 5 Points and signed with Stranger (pretty standard stuff). But the reality isn’t as sensational as “daddy paid for her record deal.”

“Her career works against the indie ideals that if you are ‘talented enough’, u can make it,” wrote Perez (Hipster Runoff, 2012), who continued to perpetuate the false narrative that LDR was a product, not an artist, with The Village Voice’s Maura Johnston adding that LDR was the “Indie Kreayshawn” i.e., a manufactured product based on YouTube views and virility, not actual musical talent (The Village Voice, 2012).

Today, the media (GQ, 2023) lovingly refers to Rob Grant as a “nepo daddy,” a meme created by LDR’s fans, but in 2012, the narrative was that LDR was Rob Grant’s nepo baby, which wasn’t true (even if Grant did admit to helping with the marketing of LDR’s debut).

In an interview with The Face in 2023, Grant — a pianist who is managed by LDR’s team in London — said that his family has been “plagued with all of these allegations,” and that, “she [LDR] had to endure all of that conspiracy theory. It’s hard for the pubic to understand that a young girl could actually have accomplished it all entirely on her own. I mean, yes, we were supportive. But the theories that were floated out there, that I bought her record label contract — absolutely absurd.”

But in 2011, Pitchfork’s Ryan Dombal was questioning whether LDR was “fetishizing” living in a trailer park when she had a “millionaire” for a father.

“My dad is an entrepreneur and an innovator,” LDR told Dombal. “Being an entrepreneur doesn’t make you a rich tycoon and being an innovator doesn’t mean that you’re successful. It just means that you’re interesting. No one cares that I lived in a [trailer] park—Dad loves trailers and is getting one in the Everglades. My first record label gave me a small check and I moved into a [trailer] park near Manhattan. It’s not something I cared to even share but people keep asking me about it. My songs are cinematic so they seem to reference a glamorous era or fetishize certain lifestyles, but that’s not my aim. I’m not trying to create an image or a persona. I’m just singing because that’s what I know how to do.”

But #LizzyGrantGate (and the various conspiracy theories that made her a hipster tabloid queen) had become the watershed moment in the shift from LDR as a new “indie” sensation to an “industry plant” that needed to be destroyed.

“They really made it their mission to destroy me,” LDR told The Quietus. “I’m not a confrontational person, so if that’s going to be my life from here on, I’d honestly rather not sing or have a career.”

Why would she care one iota about "indie credibility?" I may be old, (and perhaps this is a generation X opinion) but in the 90's we saw "indie rock" as semi-noisy/artsy/and influenced by post-punk. LDR is obviously more influenced by American Idol than Sonic Youth or Pavement. Just let the girl be a pop princess and leave it at that.